Showing posts with label coming of age. Show all posts

Showing posts with label coming of age. Show all posts

Sunday, 19 July 2015

Book Review: Go Set a Watchman - Harper Lee

Contains spoilers

A young woman takes the overnight train home to Maycomb, Alabama, for the first time in many years. Before she arrives, she makes sure to dress in slacks, in part to scandalise her aunt, in part because they are the clothes that make her feel most like herself when she returns home. The woman is Jean Louise Finch, once known as Scout, the narrator and heroine of To Kill a Mockingbird. In many ways, Maycomb is the same, but in other ways it has changed. It is the 1950s, and times are changing. Racial tensions are high, with talk of desegregation, which meets with resistance among the white members of the community. Jean Louise's homecoming is bittersweet. Maycomb is home, with all the memories of her childhood; her boyfriend is here, and her father, although her brother Jem is dead now, and Atticus is older, more creaky, but still the wise, quietly witty, respectably subversive lawyer. And Jean Louise will never see eye-to-eye with her Aunt Alexandra, and she no longer quite feels that she fits in at her hometown. There are shocks in store for Jean Louise, and everything she has previously taken for granted comes crashing down around her.

Go Set a Watchman was written before To Kill a Mockingbird, and, although it works as a sequel, being a completely new story, the elements which later evolved into the classic are visible in another form. Harper Lee brings the humour and warmth that readers will instantly recognise from Mockingbird, the same wry observation and understated wit. Jean Louise is older, but the tomboy child is never far from the surface, and Atticus, though he may seem serious, has a dry wit of his own.

The prose is inconsistent in quality; less polished than in Mockingbird, a weird combination of dry exposition and presumption that the reader to has a little more contemporary political knowledge than I had half a century later. Go Set a Watchman is character-driven, without a big major plot event such as the trial at the heart of To Kill A Mockingbird. As such, I felt it a bit less engrossing, a series of events and flashbacks, and wondering what the actual story was going to be. But when it's good, it really shines. Some lines of dialogue or description had me laughing aloud. (People who grew up in a certain kind of church will know exactly which hymn is being described as "bloodthirsty.") The characters walk onto the page fully-formed, and it's easy to forget that it was their first appearance on paper. Scout is as lovable, passionate, outrageous and unconventional as a woman as she was as a girl, a person who transcends ink and paper. The flashbacks to Scout's childhood and teenage years were very funny, as was the scene at Jean Louise's "coffee," and the way snippets of conversation from one-time acquaintances came together to be faintly ridiculous.

It doesn't really feel fair to compare the novels, except to observe how Harper Lee took the good elements of Go Set a Watchman and made them great. The change in narration from third person (Watchman) to Scout's first person (Mockingbird) brings you closer into the world, and the way that events run together in the latter, with a mixture of childish imagination and adult reality, build a complete child's view of the world out of the fragments of memory presented in Watchman.

Go Set A Watchman covers similar themes to those at the heart of To Kill a Mockingbird, of race, and justice, family, an end of innocence and Right and Wrong with capital letters. But Right and Wrong are more complex here; it is a more adult novel and leaves you, the reader, conflicted. Because here, Atticus Finch, Defender of Good and Right, a man with a sense of justice beyond his time, is wary of the changing of the times, and stands against the desegregation of the races in the South, attending meetings alongside hateful, bigoted people and condoning them with his silence.

The confrontation and conversation at the end of the book would be powerful and upsetting enough were these characters we'd met for the first time a couple of hundred pages back. With the weight of half a century behind it, however, and with literature bearing Atticus' reputation for more than twice as long as Jean Louise's twenty six years, I too felt that sense of betrayal and hurt, all the worse because Atticus remains in character throughout. His arguments against desegregation are calm, reasoned and thoughtful - and awful and wrong. It's hard to reconcile some of the terrible things he says with the man who has been long considered a hero, and I'll be posting a whole separate essay about that issue in the next day or two. There is a time when the bitterness of the rift between Jean Louise and Atticus seem impossible to get past.

Yet Go Set a Watchman ends on a note of hope and reconciliation. It has become necessary for Jean Louise to smash the idol she'd made of her father, in order to live by her own conscience, to fight battles because she knows them to be right, not to accept that everything Atticus says or does is good and right. Without wishing in any way to downplay or defend his beliefs and words, he is, for the most part, a good man, with strong morals, and a good father. The lessons she learned from him as a child and young woman set her up well for life. But he is still a man, and he is still flawed. It's as true for the reader as it is for Jean Louise; we come of age alongside her. Heroes will only lead us so far. Ultimately, we must become our own heroes.

Go Set A Watchman is not as wonderful a novel as To Kill A Mockingbird, but it was never going to be. It's a patchy, but pretty good, literary novel of its time; darker and more nuanced than its sister novel. It's interesting to compare the complex adult morality to the simple black and white of a child's understanding. Is it essential reading? Not in the same way that To Kill a Mockingbird is, but Go Set a Watchman is an interesting piece of literature, more than a first draft, but not quite a sequel, to be read thoughtfully with a critical mind.

Wednesday, 24 June 2015

A Girl of the Limberlost - Gene Stratton-Porter

"But what is a limberlost?" my childish self wondered. I was at the height of my school-story-loving days, which would place me between ten and twelve years old. I must have been at some family function, and bored, so my Grandma went to her bookshelves and found an old favourite from her own schooldays, an ancient red-covered book held together by tape, smelling of dust and vanilla. Flash forward to 2015, and A Girl of the Limberlost now sits on my own bookcase - or rather, that same antique bookcase with the glass doors, but now in my room and full of my own childhood favourites. When my Grandma moved out of her house into a retirement flat, she let me choose from a selection of her books, as well as the bookcase, and I vividly remembered enjoying this one, even if I probably didn't finish it, and didn't actually remember what the Limberlost was. (It was an area of swampland in Indiana, full of wildlife and secrets.)

A Girl of the Limberlost is a sequel to Gene Stratton Porter's novel Freckles, but I read it as a stand-alone novel and didn't feel as though I'd missed out on much. It follows Elnora Comstock, a determined young girl, as she works her way through high school, against the wishes of her loveless mother Katharine. Although the language and details had changed, the opening chapter read just like so many modern-day books for teenagers, as Elnora turns up to her new school unprepared, unfashionable and humiliated. It reminded me a lot of the start of Eleanor and Park, and I realised that although fashions may change, high school students do not.Luckily, Elnora has a kindly aunt and uncle, who are determined to make sure that she gets the upbringing and love that her mother has neglected. Katharine resents Elnora due to her being born at the same time that her husband, who she idolised, drowned in the swamp. Their fraught relationship is central to the book, and eventually Katharine comes to realise that the man she's been resenting her daughter over for sixteen or more years was not the perfect husband she has believed.

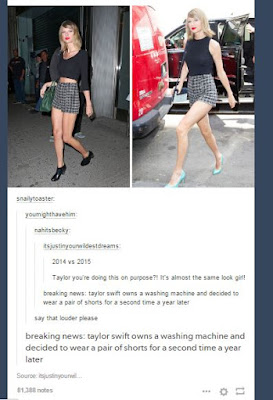

Elnora bears a few warning signs of being a turn-of-the-century paragon of virtue: generous to the poor, hard-working, beautiful and devout. But she is a very human character, one who may have an optimistic outlook, but who feels keenly her mother's neglect and the shame of being the outsider. She is proud when it comes to money, not allowing anyone to pay for her schooling but herself, which she does through selling moth and butterfly collections, and through tutoring younger children about natural sciences. She also inherits her father's talent for the violin, which she practices in secret, away from her mother, who would have none of it. But she is not so good at keeping track of her money, and when it runs out, she turns to her mother for help. This was where I thought she had a weird switch from being the Good Girl to being a bit of a brat: her high school graduation requires not one but three new dresses, but instead of buying them, her mother washes last year's white dress for her. Oh, the horror! Cue the horrified cries of "I've got nothing to wear!" and the frantic clubbing together of other friendsandrelations to customise someone else's cast-offs instead. For someone so normally thrifty, it seemed very out of character for her to throw a tantrum about wearing one white dress instead of another, but perhaps I just don't understand the importance of having a brand-new outfit for high school graduation (or perhaps prom.)

|

| If Taylor Swift can do it, so can Elnora Comstock. |

Elnora spends that summer working with a sickly young man called Philip Ammon, and they become close friends. He is engaged to another woman, a great beauty, but conveniently one who is an utter harridan, and who breaks off their engagement out of jealousy over Elnora, in front of all their friends and family. Elnora, it is implied, has developed feelings for Ammon, and as soon as his fiancee breaks up with him, he comes running back to Elnora. I didn't have a lot of patience for Ammon, finding him a bit of a drip. Like Romeo - and I don't mean that as a compliment; remember how Romeo mopes over the loss of his true love Rosaline at the beginning of the play, only to fall straight into the arms of someone he's only just met? But Elnora has more sense than to take Ammon at his word, and insists on giving him space to see if he really is over his first love. But he plays the persistent lover, which I'm not so sure is so romantic as it is intended to be. When he proposes formally to Elnora later on, her response is essentially, "Ooh, a ring, shiny! Let me try it on and see if I like it before I decide whether or not to marry you." Um... not quite sure that's a great basis on whether to marry someone or not. The whole romance element to the story is rather melodramatic and silly. A Girl of the Limberlost is not quite up there in the classic girls' coming-of-age canon with Anne, Katy and the March girls, but it is a good contemporary of them to keep them company.

Elnora spends that summer working with a sickly young man called Philip Ammon, and they become close friends. He is engaged to another woman, a great beauty, but conveniently one who is an utter harridan, and who breaks off their engagement out of jealousy over Elnora, in front of all their friends and family. Elnora, it is implied, has developed feelings for Ammon, and as soon as his fiancee breaks up with him, he comes running back to Elnora. I didn't have a lot of patience for Ammon, finding him a bit of a drip. Like Romeo - and I don't mean that as a compliment; remember how Romeo mopes over the loss of his true love Rosaline at the beginning of the play, only to fall straight into the arms of someone he's only just met? But Elnora has more sense than to take Ammon at his word, and insists on giving him space to see if he really is over his first love. But he plays the persistent lover, which I'm not so sure is so romantic as it is intended to be. When he proposes formally to Elnora later on, her response is essentially, "Ooh, a ring, shiny! Let me try it on and see if I like it before I decide whether or not to marry you." Um... not quite sure that's a great basis on whether to marry someone or not. The whole romance element to the story is rather melodramatic and silly. A Girl of the Limberlost is not quite up there in the classic girls' coming-of-age canon with Anne, Katy and the March girls, but it is a good contemporary of them to keep them company.

Sunday, 29 September 2013

Half-Sick of Shadows - David Logan

When Edward Pike and his sister Sophia were five years old, Sophia made a promise to their severe and intimidating father that she would never abandon her mother, and never leave home. And so, she never does, inferring something terrible must happen if she ever breaks her word. Even when the memory of the promise has faded, Sophia will not leave the Manse (which is a misnomer; there is no church for miles, although the house backs onto a graveyard); not to go to the next village, or to school, or visiting. At five, perhaps that is little sacrifice. As far as the twins are concerned, the Manse is the world, and the family are its people. But soon, the twins are parted when Edward is sent to boarding school. Here, he excels academically, if not socially, but the thought of Sophia and her self-imposed "curse" is never far from his mind.

What struck me most about Half-Sick of Shadows was that time does not seem to fit properly. Edward's childhood memories of the Manse read rather like a country childhood at some point in the early twentieth century. The Manse is vividly brought to life as a grim, gloomy stone house, freezing cold with no electricity and no plumbing; an isolated place miles from anywhere. Progress does come as Edward grows up, with the building of a motorway, colour television and popular culture references - but even these contain curious anachronisms, not quite fitting into a single time. Decades seem to pass in the space of ten or fifteen years of Edward's life, and I'm not convinced they can be entirely explained by the Manse being horribly old-fashioned.

"As a child, I never knew whether the world lay east, west, north or south of the Manse; I only knew that the Manse never seemed to me like part of it."Half Sick of Shadows was the joint winner of the Terry Pratchett prize or, to give its full title, the Terry Pratchett "Anywhere but here, Anywhen but now" prize. That seems to describe the Manse's setting perfectly: it is a world that is not quite the world we know, although I would be hard pressed to explain exactly why. Pratchett even drops hints (or outright spoilers) in his foreword that David Logan's novel is indeed set in an alternative universe - though "the people on an alternate Earth don't know that they are; after all, you don't."

And then you remember the strange encounter of the very first chapter, in which Edward meets a man in a so-called time machine, and wonder how you could forget such a fantastical scene which doesn't seem to lead anywhere in this brooding story about childhood, family, home, and the loss of innocence. The event lingers as a shadowy memory, another example of something uncanny about Edward's world, but as you read about his ordinary life, his family, his schooldays and aspirations and everyday struggles, like him, you almost forget.

"The mystery of the stranger and his time machine puzzled me for as long as the memory of it lasted, which, when you're stupidly young, isn't long. I'd more or less forgotten about it by strawberry jam on toast and sweet tea time."Half-Sick of Shadows defies genre classification, containing some elements of science fiction and horror, but not enough of either to describe it accurately. The story's potential overflows out of the 363 pages which make up the novel. Whole chapters, perhaps even more volumes, could be filled with the subplots and almost-unanswered questions. Logan divides Edward's life into three segments: "Before Alf," "The Alf Years" and "Alf Unleashed" - Alf being Edward's mysterious schoolfellow that only he seems able to see, and who might or might not be exactly real. As far as the narrative is concerned, Alf is the defining feature of Edward's childhood and youth, but Edward himself does not seem to notice him until the final section, when his role in Edward's life is revealed.

I felt that the novel was let down a little by its final hundred pages or so. The story seemed to get a little carried away, as Edward and his family get embroiled deeper and deeper in too many macabre plot turns, which were rushed through at top speed. It was all a bit too much. Aside from that quibble, Half-Sick of Shadows is a gothic masterpiece: shifting, shadowy, unsettling and occasionally shocking. It is beautifully written, poignant and poetic, and really captures a child's understanding of the world, which, though it may not be informed by the necessary knowledge to be quite accurate, is logical in its own way, and makes perfect sense to the perceiver.

If you enjoyed this, you might like:

The Ocean at the End of the Lane - Neil Gaiman

The Earth Hums In B Flat - Mari Strachan

Friday, 30 August 2013

15 Day Book Blogger Challenge: Day Thirteen

Day 13: Describe one underappreciated book EVERYONE should read.

This is a difficult one. Everyone? I am well aware how different everyone's reading tastes are, so instead I will offer two.

Tell The Wolves I'm Home by Carol Rifka Brunt quietly slipped into the bookshops and libraries earlier this year with the minimum of fuss, but really deserves to have been noticed. It's a quiet sort of story about a teenage girl coming to terms with the death of her beloved uncle. It is a thoughtful, very honest story about family, loneliness, art, unrequited love and growing up, with a family portrait as the centrepiece.

Redshirts by John Scalzi is a must-read for Star Trek fans, or indeed anyone familiar with the trope of the expendable extra whose only function in a story is to die horribly in order to give a sense of peril to the plot. This is their story. The tagline on the front cover reads: "They were expendable... until they started comparing notes."

Warning: this book causes idiotic giggling. Read in public at your own peril! Redshirts is a wonderful parody, "recursive and meta" and completely annihilates the Fourth Wall. I'm not sure if it's objectively good, or whether I enjoyed it because I stumbled upon it at the same time I found myself inadvertantly and bewilderedly falling in love with Star Trek, but it is very clever and the most fun I've had from a book in a long time.

Thursday, 16 May 2013

Bout of Books: Thursday

Today was another slow day at work, with not enough jobs to keep me occupied all day, and for the second day in a row, the weather meant customers were few and far between. Yesterday, because it was pouring with rain and today because the sun was out and no doubt people were all on the beach, in the park or in their gardens. The upside of this was that today, I got to escape the dingy staff room and take my lunch and book out to the nearby park, stopping off at the local bakery, Grace's, for a take-away coffee and a tasty doughnut. I was incredibly lucky: there was a heavy-looking grey cloud hovering ominously over the town, but the sky over the park was blue and sunny. Even when the cloud started to creep towards me, there remained a friendly blue patch right over my bench. Needless to say, it was very difficult to head back to work afterwards.

I'm about three quarters of the way through Alex Woods, and for all its apparent simplicity, it is an extremely profound book. Picking up from yesterday, we've followed Alex through his early teens, his friendship with the curmudgeonly Mr Peterson, his struggles with school bullies, morality and family. Alex Woods is a very cleverly crafted story. Every incident is there for a purpose, though not apparent at first, coming together to shape Alex's character and build up to the main event of the plot. For a long time, I felt that Alex read quite young for his age: he has a lot of book-knowledge, but there was a kind of innocence in his earnestness which, though very endearing, made me think of a twelve-year-old when he was approaching fifteen. Then something happens to make him grow up subtly but quickly. All the little events in preceding chapter that have taught him about himself and the world, come together to show that he is a young man with a strength of will beyond his years.

Tomorrow will be a very welcome day off, and I've made few plans other than reading plenty. I intend to finish Alex Woods either tonight or tomorrow, and make the most of the day to make a start on Alan Moore's graphic novel Watchmen. I've had this out of the library for a while, but needed the time to really get stuck into reading it. Tomorrow is the perfect opportunity.

Books read today: The Universe Versus Alex Woods - Gavin Extence

Number of pages read today: 120

Number of books read in total: 2

Books finished: 1

Today #insixwords: light, easy read but surprisingly deep

Books finished: 1

Today #insixwords: light, easy read but surprisingly deep

Books added to mental shopping list: 5

Labels:

bout of books,

coming of age,

literary fiction,

readathon

Wednesday, 15 May 2013

Bout of Books: Tuesday and Wednesday

Apologies for the lack of update yesterday. After work I went out with friends to see the new Star Trek movie. I'm new to Star Trek, having somewhat reluctantly seen the rebooted films (once you get into Star Trek, surely there is no going back!) but it was an excellent film. As with a lot of fantasy, and increasing amount of science fiction, it appealed to my longing for exploration and adventure. I can see that I'm going to have to borrow some of my friend's original series DVDs. Oh dear. What have I done?

Yesterday lunchtime I finished The Age of Miracles. While remaining a fascinating premise, there came a point about three-quarters of the way through when it stopped being fun, and became just plain depressing. If events could go one of two ways: good or bad, bad or terrible, invariably the worst-case scenario would happen. The book was powerful, poetic and eerie, a solemn voice in an unnatural hush, but ultimately it was a relief to reach the end.

Memorable quotes:

"Amid this usual bilge now floated a different kind of gossip, its sources equally dubious. In 1562, a scientist named Nostradamus had predicted that the world would end on this exact day."I include this quote because when I was thirteen, I remember that exact same rumour going around my middle school. (I can even tell you the date, because I wrote dismissively about it in my diary: 4th July 1999. Of course, this was the year of the Millennium Bug scares - that everything technological would fail on the stroke of midnight because it would think the year was 1900, and stop working because it would think it hadn't been invented yet.)

"doesn't every previous era feel like fiction once it's gone?"

"Birds have always been messengers. After the flood, it was a dove holding an olive branch that told Noah the flood was over. That's how he knew he could leave the ark. Think about that. Our birds aren't carrying any olive branches. Our birds are dying."

As I had forgotten to take a second book to work with me to read on my lunch break, I swapped The Age of Miracles for Gavin Extence's The Universe Versus Alex Woods in the staffroom library. I liked Alex straight away, a bright but innocent teenager arrested on re-entering the country and found with an urn of the ashes of his friend, Mr Peterson, and a large quantity of marijuana. Alex narrates the events with a kind of curious detachment, before deciding to start his story from a strange event in his childhood: when he was hit in the head by a meteorite, and survived.

Readathon statistics:

Books read today: The Age of Miracles - Karen Thompson Walker,

The Universe Versus Alex Woods - Gavin Extence

Number of pages read today: 114

Number of books read in total: 2

Books finished: 1

Today #insixwords: No updates yesterday because Star Trek

Books finished: 1

Today #insixwords: No updates yesterday because Star Trek

Cinema ice cream: mint choc chip

Wednesday 8.30PM

Oh, boy, it's been a long day. Work yesterday was a horrible mixture of manic panic and deadly boredom - all or nothing and everything going wrong which played havoc with my brain. Looking back, I can't think of any one thing that made it a terrible day, but a combination of little annoyances left me feeling dead on my feet, which carried on into today. I spent most of today staring into space while trying to look as though I wasn't just staring into space, but I didn't really have to pretend because we had very few customers. I welcomed the few who wanted to talk at great length about books (not so much the ones who wanted to discuss their medical issues, but even they were a distraction. I must have a face that says you can tell me all your problems. And I do like to get to know my customers as people, and some of the older ones don't have many people to talk to, so if I can lend a sympathetic ear, that's all good.)

Read a little more of Alex Woods at lunch time, where I saw his twelve-year-old self being chased by bullies into a random stranger's greenhouse, being blamed for the destruction of this greenhouse, and being forced to make amends to the stranger by doing various chores for him. Thus begins the friendship between Alex Woods and Mr Isaac Peterson, an elderly Vietnam war veteran and widower.

Mr Peterson has an extensive collection of the works of Kurt Vonnegut, who, by coincidence, is one of the authors of a book on my to-read pile, lent to me by the husband of my friend. Alex Woods has managed to push Cat's Cradle higher up the to-read pile. I love books which make me curious about other literature (also music, film or obscure subjects.)

Readathon statistics:

Books read today: The Universe Versus Alex Woods - Gavin Extence

Number of pages read today: 136

Number of books read in total: 2

Books finished: 1

Today #insixwords: Can't wait till my day off

Books finished: 1

Today #insixwords: Can't wait till my day off

Length of after-work nap: 40 minutes

Friday, 26 April 2013

Tell The Wolves I'm Home - Carol Rifka Brunt

Sometimes you only have to pick up a book to know it's going to be something special. I'd never heard of Carol Rifka Brunt's novel Tell The Wolves I'm Home when I found it at work the other day, and yet I knew before I even read the cover blurb that it had the potential to be a good friend. Maybe it's the wistful dreaminess of the title, or the striking, bright green cover design. I prefer to think that it was some kind of magic inside the book itself, calling out to me, knowing that it had found a kindred spirit.

I returned to look at this book several times while working in the bookshop, and when I found a shiny new copy in the library a few days later, I knew it was meant to be. Tell The Wolves I'm Home is the story of an introverted teenage girl, June, dealing with the death of her uncle Finn, who was her closest friend and confidant, from AIDS. Through her grief, she strikes up an unlikely secret friendship with Toby, Finn's partner, and gets to know her uncle better through Toby's memories.

Tell The Wolves is a story about love and loss, but also of finding, growing up, death and life, loneliness and jealousy, but at its heart, it is a tale of family. The book brings the reader into June's family, and gradually, although the primary relationship is between June and Finn - both living and dead - it becomes clear that the bond between June and her sister Greta is as important, or, I would argue, even more so. The sisters were close as children, but in their teenage years have grown apart. Greta appears at first as that familiar figure, the mean elder sister; the grumpy, rebellious teenager who can't help but pick on her shyer younger sister. But the reader comes to realise, long before June does, that Greta is lonely too. Greta starts off as a background figure in the novel, which is how June sees her; while she is so preoccupied with the absence of Finn, she misses the sister who is right beside her, trying in a clumsy way to reach out to her. June and Greta echo the fragile and fractured relationship between Finn and their mother Danni, who was his sister. Once close, they had let secrets, jealousy and resentment come between them, never to be fully resolved.

Finn was once a famous artist, but one who disappeared from public life some time ago. His final work is a portrait of June and Greta, which is the object at the centre of the novel. The painting lives on as Finn's legacy, and is added to by all those who loved the artist most, becoming a collaborative work containing parts of each of them. Tell The Wolves I'm Home demonstrates how each person's life touches many others, how we are formed by the relationships we make and the people we meet. After Finn's death, June discovers that many of his quirks and traits had originated from Toby, and in turn, she sees much of Finn in Toby. Perhaps because of this, I found it a bit difficult to view Toby and Finn as separate characters, and wondered whether June was looking for a substitute Finn in her new friendship with Toby, an issue that is addressed in the novel.

June is a thoughtful girl and mature for her age, so it would come as a bit of a shock whenever I was reminded that after all, she is still very young. Fourteen is a strange age when one is part child, part adult, and sometimes the two parts don't sit well together at all. The busyness of June's parents make it easier for her to take the train from the suburbs into New York City without their knowledge, and a couple of times I wondered why the secrecy? Surely it would be better to discuss Toby, Finn and all the unresolved issues between the families as adults, though they may have to get through some unpleasantness first? And then I remembered that they aren't all adults. I remembered how powerless you are at fourteen. If adults say no, they won't discuss something, then you can't make them. They can stop you seeing someone, going somewhere, doing anything. Finn (and later Toby) was the exception in treating June as an equal.

Tell The Wolves I'm Home touched me close to the heart. June reminded me of myself as a teenager - shy and always an outsider, though I think that despite her quietness she had more confidence in herself as a person than I did at her age. The story, too, reminded me of the stories I would write in my teens - which is not in itself a recommendation, as I was inclined towards the sentimental and the morbid. Carol Rifka Brunt avoids crossing the line into sentimentality with her lyrical prose and strong characters and relationships. Tell The Wolves I'm Home is a very beautiful, very human story, and I closed the book with reluctance. The best new book I've read this year so far. I will be buying my own copy of this book, and it will take its place on my "favourites" shelf.

If you enjoyed this, you might like:

When God was a Rabbit - Sarah Winman

A Place of Secrets - Rachel Hore

Paper Towns - John Green

Eve Green - Susan Fletcher

The Earth Hums in B Flat - Mari Strachan

Labels:

1980s,

5 buttons,

coming of age,

death,

family,

favourite,

lgbt,

new author,

secrets,

teenage

Saturday, 18 February 2012

February mini-reviews.

Hi everyone. Despite my lack of blog posts recently, I've actually been reading a lot, I just haven't had an awful lot to say about any of the books. However, I felt it was about time to share some thoughts on a few of the things that I've been reading.

Sandman - Neil Gaiman

Since discovering that one of the Island libraries has nearly all of the Sandman graphic novels, I have been making regular trips and marching through the series, before passing them on to my friend. There is a wide variety in the style and format of stories, like an elaborate patchwork quilt: one volume will be a long narrative, and the next made up of short stories. Some star the titular Sandman, Dream, and his Endless siblings: Destiny, Death, Delirium, Desire, Despair and Destruction, whereas in other volumes they only appear occasionally, around the edges of the stories, so to speak.

Since discovering that one of the Island libraries has nearly all of the Sandman graphic novels, I have been making regular trips and marching through the series, before passing them on to my friend. There is a wide variety in the style and format of stories, like an elaborate patchwork quilt: one volume will be a long narrative, and the next made up of short stories. Some star the titular Sandman, Dream, and his Endless siblings: Destiny, Death, Delirium, Desire, Despair and Destruction, whereas in other volumes they only appear occasionally, around the edges of the stories, so to speak.

I'm currently up to vol. 8: Worlds' End, in which travellers from all through time, space and contradictory but co-existing realities find themselves stranded by a storm in an Inn, in which they occupy their time by telling stories of all flavours and styles. But the storm is not an ordinary storm, but a "reality storm" caused by something strange and rare and unexplained. When the tales have all been told, the travellers go to the window and see a strange thing in the sky, a thing that none could explain or understand, but somehow we all, reader and character alike, could sense that things were never going to be the same again. Behind the pages of the stories told in Worlds' End, another story has been taking place, a story of enormous significance, hidden from the eyes of the ordinary - extraordinary - folk who dwell in the Sandman universe(s) and yet to be revealed to the readers, no doubt in volume 9.

By this point, Sandman has become more than "just a comic book" to be a masterpiece of storytelling, in any format.

Submarine - Joe Dunthorne

Submarine is a coming-of-age tale of Oliver Tate, a precocious teenage boy, an account of his relationships with family, friends and girls, and his observations of the world around him. It is an intelligent, somewhat poetic read, and one which led me back to my Superior Person's Book of Words to indulge the word-nerd tendencies that I share with the narrator. However, I didn't altogether like Oliver - he was a rather obnoxious kid - and the scenes in which he participated in the bullying of a classmate were an insurmountable barrier between me and the book, and Dunthorne seemed to rely too much on cringe-comedy and explicit content for my tastes - possibly appropriate for a tale about a teenage boy. I'm not saying that I entirely disliked Submarine, but I don't feel that I have gained anything from having read it, and shan't be rereading or watching the film.

Submarine is a coming-of-age tale of Oliver Tate, a precocious teenage boy, an account of his relationships with family, friends and girls, and his observations of the world around him. It is an intelligent, somewhat poetic read, and one which led me back to my Superior Person's Book of Words to indulge the word-nerd tendencies that I share with the narrator. However, I didn't altogether like Oliver - he was a rather obnoxious kid - and the scenes in which he participated in the bullying of a classmate were an insurmountable barrier between me and the book, and Dunthorne seemed to rely too much on cringe-comedy and explicit content for my tastes - possibly appropriate for a tale about a teenage boy. I'm not saying that I entirely disliked Submarine, but I don't feel that I have gained anything from having read it, and shan't be rereading or watching the film.

When I first read the series a couple of years ago, I wrote, "I'm not sure that The Hunger Games is as amazing as the hype had led me to believe, but it is a very good book, and it was a lot better than the book blurb and my reading taste came together to expect." Catching Fire won me over, and evidently the story lingered in my brain, because over the last months I've had dream after dream about being in that arena, about being Katniss Everdeen. With the hype mounting for the new film which comes into cinemas next month, I am still undecided whether or not I actually want to see it.

When I first read the series a couple of years ago, I wrote, "I'm not sure that The Hunger Games is as amazing as the hype had led me to believe, but it is a very good book, and it was a lot better than the book blurb and my reading taste came together to expect." Catching Fire won me over, and evidently the story lingered in my brain, because over the last months I've had dream after dream about being in that arena, about being Katniss Everdeen. With the hype mounting for the new film which comes into cinemas next month, I am still undecided whether or not I actually want to see it.

The trailer is amazing. Watching it, I felt tears stab at my eyes a couple of times, when Katniss shouts in desperation and love for her sister: "I volunteer!" and the salute to her from the citizens of District 12. And yet - there is a movie already in my mind that I feel a fierce attachment and loyalty to. Flicking through The Tribute Guide which came into bookstores recently, I nearly shouted aloud, "You are NOT President Snow!" (Donald Sutherland is an excellent actor and I am sure he will play the part admirably, but he is not my President Snow.) Some pictures looked perfect, while others I judged as "too sci-fi." Jennifer Lawrence is almost Katniss, Josh Hutcherson a passable Peeta, Gale I never had a very strong image of, so he'll do. Rue. Cinna. Effie Trinket. Prim. All fine. Great, even. It looks a like a great movie.

Wish Me Luck - Margaret Dickinson

I picked up this cosy wartime romance in a charity shop years ago, and forgot that I'd even got it until yesterday, when I wanted a break from the doom and gloom of Panem. I have little time for romance, whether that be Mills and Boon, or chick lit, but occasionally I'll make an exception for a sweet story from the "granny" section of the bookstore, wartime romances, family sagas, usually seeming to take place in World War 2 Liverpool. Wish Me Luck is the story of Fleur, a WAAF (women's branch of the Royal Air Force) girl who falls in love with an RAF officer. Their relationship is marred, not only by the dangers of being in love during wartime, but by their parents, whose own pasts are intertwined by secrets long gone but never forgotten.

I picked up this cosy wartime romance in a charity shop years ago, and forgot that I'd even got it until yesterday, when I wanted a break from the doom and gloom of Panem. I have little time for romance, whether that be Mills and Boon, or chick lit, but occasionally I'll make an exception for a sweet story from the "granny" section of the bookstore, wartime romances, family sagas, usually seeming to take place in World War 2 Liverpool. Wish Me Luck is the story of Fleur, a WAAF (women's branch of the Royal Air Force) girl who falls in love with an RAF officer. Their relationship is marred, not only by the dangers of being in love during wartime, but by their parents, whose own pasts are intertwined by secrets long gone but never forgotten.

Wish Me Luck is a light, easy read. Dickinson's style is simple but warm. She hooked me with the mysteries and kept the plot twisting so that it wasn't predictable. She recreates 1940s Lincolnshire and Nottingham well, peopled with a likeable, well-rounded cast. With one exception. Fleur's mother was too unpleasant, a bitter, shrieking harridan who is never given much development or redemption, and towards the end, I felt that the story tailed off a little. Of course it is inevitable that any book set on the home front of World War 2 is going to feature some sort of tragedy, but it all seemed to come at once, like an avalanche of heartbreak, all at once. Still, Wish Me Luck is a very sweet, "nice" sort of story over all, and despite the deluge of disaster before the happy ending, just the sort of book to cheer me up when I was feeling low.

Sandman - Neil Gaiman

Since discovering that one of the Island libraries has nearly all of the Sandman graphic novels, I have been making regular trips and marching through the series, before passing them on to my friend. There is a wide variety in the style and format of stories, like an elaborate patchwork quilt: one volume will be a long narrative, and the next made up of short stories. Some star the titular Sandman, Dream, and his Endless siblings: Destiny, Death, Delirium, Desire, Despair and Destruction, whereas in other volumes they only appear occasionally, around the edges of the stories, so to speak.

Since discovering that one of the Island libraries has nearly all of the Sandman graphic novels, I have been making regular trips and marching through the series, before passing them on to my friend. There is a wide variety in the style and format of stories, like an elaborate patchwork quilt: one volume will be a long narrative, and the next made up of short stories. Some star the titular Sandman, Dream, and his Endless siblings: Destiny, Death, Delirium, Desire, Despair and Destruction, whereas in other volumes they only appear occasionally, around the edges of the stories, so to speak.I'm currently up to vol. 8: Worlds' End, in which travellers from all through time, space and contradictory but co-existing realities find themselves stranded by a storm in an Inn, in which they occupy their time by telling stories of all flavours and styles. But the storm is not an ordinary storm, but a "reality storm" caused by something strange and rare and unexplained. When the tales have all been told, the travellers go to the window and see a strange thing in the sky, a thing that none could explain or understand, but somehow we all, reader and character alike, could sense that things were never going to be the same again. Behind the pages of the stories told in Worlds' End, another story has been taking place, a story of enormous significance, hidden from the eyes of the ordinary - extraordinary - folk who dwell in the Sandman universe(s) and yet to be revealed to the readers, no doubt in volume 9.

|

| I felt almost afraid to turn the page, fascinated but scared of what I might see in the sky. |

Submarine - Joe Dunthorne

Submarine is a coming-of-age tale of Oliver Tate, a precocious teenage boy, an account of his relationships with family, friends and girls, and his observations of the world around him. It is an intelligent, somewhat poetic read, and one which led me back to my Superior Person's Book of Words to indulge the word-nerd tendencies that I share with the narrator. However, I didn't altogether like Oliver - he was a rather obnoxious kid - and the scenes in which he participated in the bullying of a classmate were an insurmountable barrier between me and the book, and Dunthorne seemed to rely too much on cringe-comedy and explicit content for my tastes - possibly appropriate for a tale about a teenage boy. I'm not saying that I entirely disliked Submarine, but I don't feel that I have gained anything from having read it, and shan't be rereading or watching the film.

Submarine is a coming-of-age tale of Oliver Tate, a precocious teenage boy, an account of his relationships with family, friends and girls, and his observations of the world around him. It is an intelligent, somewhat poetic read, and one which led me back to my Superior Person's Book of Words to indulge the word-nerd tendencies that I share with the narrator. However, I didn't altogether like Oliver - he was a rather obnoxious kid - and the scenes in which he participated in the bullying of a classmate were an insurmountable barrier between me and the book, and Dunthorne seemed to rely too much on cringe-comedy and explicit content for my tastes - possibly appropriate for a tale about a teenage boy. I'm not saying that I entirely disliked Submarine, but I don't feel that I have gained anything from having read it, and shan't be rereading or watching the film.

The Hunger Games - Suzanne Collins (reread)

When I first read the series a couple of years ago, I wrote, "I'm not sure that The Hunger Games is as amazing as the hype had led me to believe, but it is a very good book, and it was a lot better than the book blurb and my reading taste came together to expect." Catching Fire won me over, and evidently the story lingered in my brain, because over the last months I've had dream after dream about being in that arena, about being Katniss Everdeen. With the hype mounting for the new film which comes into cinemas next month, I am still undecided whether or not I actually want to see it.

When I first read the series a couple of years ago, I wrote, "I'm not sure that The Hunger Games is as amazing as the hype had led me to believe, but it is a very good book, and it was a lot better than the book blurb and my reading taste came together to expect." Catching Fire won me over, and evidently the story lingered in my brain, because over the last months I've had dream after dream about being in that arena, about being Katniss Everdeen. With the hype mounting for the new film which comes into cinemas next month, I am still undecided whether or not I actually want to see it. The trailer is amazing. Watching it, I felt tears stab at my eyes a couple of times, when Katniss shouts in desperation and love for her sister: "I volunteer!" and the salute to her from the citizens of District 12. And yet - there is a movie already in my mind that I feel a fierce attachment and loyalty to. Flicking through The Tribute Guide which came into bookstores recently, I nearly shouted aloud, "You are NOT President Snow!" (Donald Sutherland is an excellent actor and I am sure he will play the part admirably, but he is not my President Snow.) Some pictures looked perfect, while others I judged as "too sci-fi." Jennifer Lawrence is almost Katniss, Josh Hutcherson a passable Peeta, Gale I never had a very strong image of, so he'll do. Rue. Cinna. Effie Trinket. Prim. All fine. Great, even. It looks a like a great movie.

But I'm still not certain. The concept of the book - children killing each other for entertainment purposes - repelled me, and watching it as a film takes you closer to the real experience, the discomfort of knowing you'll be watching the Hunger Games recreated, rather than reading about them. (Maybe that's just me.) And the other thing: I have a phobia of wasps - can't even say or type the word without flinching, and there is a horrific scene with mutant wasps, or "tracker-jackers." Is this spheksophobia strong enough to deter me from watching the film?

Reading The Hunger Games the second time around, I realise that Katniss' affections could go either way, being manipulated and fabricated before she's really aware that she has any romantic feelings, being formed by her circumstances. Interestingly, on my first time reading the books, if I had any strong opinions on the matter, I suppose I was slightly in favour of Team Peeta, whereas this time I'm veering more towards Team Gale. I wonder what has changed.

I picked up this cosy wartime romance in a charity shop years ago, and forgot that I'd even got it until yesterday, when I wanted a break from the doom and gloom of Panem. I have little time for romance, whether that be Mills and Boon, or chick lit, but occasionally I'll make an exception for a sweet story from the "granny" section of the bookstore, wartime romances, family sagas, usually seeming to take place in World War 2 Liverpool. Wish Me Luck is the story of Fleur, a WAAF (women's branch of the Royal Air Force) girl who falls in love with an RAF officer. Their relationship is marred, not only by the dangers of being in love during wartime, but by their parents, whose own pasts are intertwined by secrets long gone but never forgotten.

I picked up this cosy wartime romance in a charity shop years ago, and forgot that I'd even got it until yesterday, when I wanted a break from the doom and gloom of Panem. I have little time for romance, whether that be Mills and Boon, or chick lit, but occasionally I'll make an exception for a sweet story from the "granny" section of the bookstore, wartime romances, family sagas, usually seeming to take place in World War 2 Liverpool. Wish Me Luck is the story of Fleur, a WAAF (women's branch of the Royal Air Force) girl who falls in love with an RAF officer. Their relationship is marred, not only by the dangers of being in love during wartime, but by their parents, whose own pasts are intertwined by secrets long gone but never forgotten.Wish Me Luck is a light, easy read. Dickinson's style is simple but warm. She hooked me with the mysteries and kept the plot twisting so that it wasn't predictable. She recreates 1940s Lincolnshire and Nottingham well, peopled with a likeable, well-rounded cast. With one exception. Fleur's mother was too unpleasant, a bitter, shrieking harridan who is never given much development or redemption, and towards the end, I felt that the story tailed off a little. Of course it is inevitable that any book set on the home front of World War 2 is going to feature some sort of tragedy, but it all seemed to come at once, like an avalanche of heartbreak, all at once. Still, Wish Me Luck is a very sweet, "nice" sort of story over all, and despite the deluge of disaster before the happy ending, just the sort of book to cheer me up when I was feeling low.

Labels:

comic book,

coming of age,

cosy,

dystopia,

graphic novel novice,

hunger games,

literary,

mixing it up,

romance,

sandman,

world war 2

Wednesday, 7 December 2011

Will Grayson, Will Grayson/Dash and Lily's Book of Dares

Will Grayson, Will Grayson: John Green and David Levithan

Will Grayson, Will Grayson: John Green and David LevithanI'd read a lot about John Green on young adult book review blogs, and the general consensus was that I ought to go out and buy all of his books! So, gift card in hand I wandered down the road to the other bookshop and perused the shelves. Should I go for An Abundance of Katherines, about a boy who only dates Katherines - because guess what? Katie is short for Katherine. Or Looking for Alaska? In the end I was won over by Will Grayson, Will Grayson's shiny cover and the novelty of the idea of two main characters with the same name - Will Grayson.

The book is written in the first person, alternating between the two Wills, with each author taking on a particular Will Grayson. Both Wills are quite lonely individuals. The first tries to live quietly and unobtrusively, his two rules being "Don't care" and "Shut up," out of fear of getting hurt. To his dismay, his best friend, Tiny Cooper - who he isn't even sure he likes very much - is the exact opposite, big, loud and flamboyant, falling in love every other day and the writer, director and star of a school musical - about his own life!

The other Will Grayson is clinically depressed and trapped in a state of self-loathing, putting up barriers between himself and the world. I've read a lot of reviews where people have found Will 2 to be moody and unlikeable, but I felt that he was a very real character who I could identify strongly with. The two Wills meet by chance in Chicago, and their lives change and take on new directions, in a rollercoaster of a story that is at times hilarious, heartbreaking and really, really corny - but in such a way that you can't help but grin.

Despite the title of the book, it is really Tiny Cooper who is the central character, and plays a crucial role in both Wills' lives. At first seeming to be a lovable but somewhat stereotypical "gay best friend" supporting role, gradually you come to realise that this boy has a huge heart beneath all his posturing, someone who genuinely lives to try to make other people feel better about themselves. He was truly lovely.

Because both Wills were written by different authors, I found it interesting to see how the characters were alike, and how they were different. In many ways, their "journeys of self-discovery" echoed each other's, but not in a self-conscious way. There were two authors, each writing their own version of a coming-of-age story, so their characters had both similarities and differences that came across more realistically than if a single author were to assign different characteristics to the different narrators.

While reading Will Grayson. I was surprised to find a little handwritten note inside, from somebody named Alicia, advising me to look at John Green and his brother's vlog site at Youtube, and recruiting me into their "nerdfighters' army." I was ridiculously excited that someone was passionate enough about her favourite author to want to share her love of reading with random strangers in a bookshop like this, and it led me to think of reviews I had read of one of David Levithan's other co-authored books:

Dash and Lily's Book of Dares: Rachel Cohn and David Levithan.

Dash is browsing the bookshop one Christmas vacation, when among his favourite author's books, he finds a little red notebook with messages in code from a girl named Lily. Instead of merely contacting her with his personal details, he leaves a dare for her in ret

urn, and so the game begins.

Like Will Grayson, this book is written in alternating chapters: one narrated by Lily, the other by Dash. It's a light-hearted, cheerful and hilarious festive read - I kept laughing out loud on the train and ferry - and a sweet, heartwarming romance. Dash and Lily are loveable, nerdy characters - he is a word nerd, she's a strange, lonely girl, both more or less home alone for Christmas. Their dare game takes them all across New York: through the bookshop, Santa's grotto, nightclubs and Madame Tussauds, with the aid of friends and relations working in each place. Yes, there are a lot of unlikely coincidences and contrivances, but it is another cosy, feel-good novel for the Christmas season.

Labels:

co-authored books,

coming of age,

feel-good,

festive,

friendship,

lgbt,

romance,

teen,

ya

Wednesday, 9 March 2011

Norwegian Wood, Haruki Murakami

Whenever Toru Watanabe hears his favourite Beatles song, “Norwegian Wood,” his mind is taken back to the late 1960s, when he was a student in Tokyo. In particular he relives his relationships with two girls: vulnerable, damaged Naoko, the girlfriend left behind by his best friend Kizuki, who took his own life aged 17, and lively, curious Midori who is Naoko’s opposite in every way.

Whenever Toru Watanabe hears his favourite Beatles song, “Norwegian Wood,” his mind is taken back to the late 1960s, when he was a student in Tokyo. In particular he relives his relationships with two girls: vulnerable, damaged Naoko, the girlfriend left behind by his best friend Kizuki, who took his own life aged 17, and lively, curious Midori who is Naoko’s opposite in every way.Norwegian Wood is first and foremost a story about memory. It’s quite difficult to comment on the prose, as being a book in translation, I’m not sure whether to credit the author Murakami, or translator Jay Rubin. Still, the narration is beautiful and poetic. In the descriptions, I felt the effect of a lazy, sultry summer afternoon, as if lying in a meadow and watching the world go by. There is a haunting sense of the sadness of time gone by, lost loves and missed opportunities.

In Watanabe we have a protagonist who is drifting, unsure of what he wants to do with his life. He is an ordinary youth at a time of revolution: he watches his fellow students protest about the “established order,” then slink back to class so as not to fail their course. Watanabe is a student of drama, more out of a vague curiosity than because he has any passion for the subject, a rather world-weary, bored character who describes university as “a period of training in techniques for dealing with boredom.” He is somewhat of a loner, going through to high school making up a third with Kizuki and Naoko. After Kizuki’s death, he and Naoko clung together as if for safety, but when they have spent only one year at university, Naoko takes “leave of absence” and is taken to a sanatorium for mental health.

When compared with Naoko, Watanabe himself, or anyone else, Midori stands out as someone fully alert and alive amongst a cast of sleepy drifters. She is rather a breath of fresh air, a childlike character in her curiosity and frankness. Despite being rather sex-obsessed and starting horribly inappropriate conversations at the worst times, there is a sort of innocence about Midori that is very endearing in a world of “phonies.”

compared with Naoko, Watanabe himself, or anyone else, Midori stands out as someone fully alert and alive amongst a cast of sleepy drifters. She is rather a breath of fresh air, a childlike character in her curiosity and frankness. Despite being rather sex-obsessed and starting horribly inappropriate conversations at the worst times, there is a sort of innocence about Midori that is very endearing in a world of “phonies.”

compared with Naoko, Watanabe himself, or anyone else, Midori stands out as someone fully alert and alive amongst a cast of sleepy drifters. She is rather a breath of fresh air, a childlike character in her curiosity and frankness. Despite being rather sex-obsessed and starting horribly inappropriate conversations at the worst times, there is a sort of innocence about Midori that is very endearing in a world of “phonies.”

compared with Naoko, Watanabe himself, or anyone else, Midori stands out as someone fully alert and alive amongst a cast of sleepy drifters. She is rather a breath of fresh air, a childlike character in her curiosity and frankness. Despite being rather sex-obsessed and starting horribly inappropriate conversations at the worst times, there is a sort of innocence about Midori that is very endearing in a world of “phonies.”Immediately after I jotted down that thought, a throwaway line from Midori jogged my suspicions as it echoed from another character’s history, and I expected a plot twist that never came to pass – much to my relief, for it would have completely changed my feelings towards one of the most central characters, and not for the better.

|

| Read for the Support Your Local Library 2011 challenge |

Usually, love triangles bore me, and I have little patience with a character torn between two people. If it’s not obvious who you should be with, I reason, then should you be with either? In Norwegian Wood, however, I felt sympathy with Toru Watanabe’s dilemma. Naoko and Midori were so different, yet both were such important parts of his life. His choice seemed so impossible.

Norwegian Wood is the first book I have read by Haruki Murakami, and it is described as being very different from his usual style – a coming-of-age novel and a romance – or several romances. I understand that most of his books have more surreal or supernatural elements to them – but this is something I would be perfectly happy to find out for myself.

Norwegian Wood has been made into a film which is released in the UK on Friday.

Labels:

1960s,

4*,

bildungsroman,

coming of age,

Japan,

literary,

love triangle,

romance,

Support Your Local Library

Friday, 18 February 2011

Artichoke Hearts, Sita Brahmachari

Mira Levenson has just turned twelve and her world is becoming a strange and unrecogniseable place. Her Nana Josie, always so artistic, passionate and full of life, is dying; she can't stop thinking about Jidé Jackson, whose confident, joky manner hides a tragic history and a sensitive soul. Mira is changing. Sometimes she catches her mouth saying what she didn't intend to say, speaking out when she's always been so shy, or alternatively keeping secrets to herself. Nothing particularly drastic, she just doesn't feel like sharing everything with everybody.

Artichoke Hearts is a pensive, sometimes sad read, but ultimately it left me feeling uplifted, a celebration of life, youth, a loving family and good friends. I would recommend it for Judy Blume fans and older readers of Jacqueline Wilson, who are maybe looking for something a bit more grown-up. So far, Artichoke Hearts has quietly slipped onto the bookshop shelves with little fanfare, but it deserves to be widely read and talked about.

There are a lot of books for teenagers that deal with the aftermath of the death of a loved one. Artichoke Hearts actually seemed to be targetted at the younger end of the Young Adult range (11+) but is unusual in exploring a terminal illness, and the feelings of helplessness of those who can only watch as a relative approaches death, and Brahmachari writes this with simplicity but a great deal of maturity. Nana Josie is early on established as a vivacious, artistic woman, a former hippy and passionate protester. Early on, there is a moment of dark, uncomfortable humour, as she embarks on her big artistic project: to paint her own coffin. It is heartbreaking to watch such a lively person fade.

The artichoke of the title refer to a charm given to Mira by Nana Josie, a symbol of the human heart, and how with age and experience, a heart which may seem to break grows tough layers to protect it, like the layers of an artichoke. The novel is a sweet, beautiful coming-of-age story, showing a child starting to learn who she is. Mira is a quiet girl, artistic and thoughtful, but through the sadness of seeing her grandmother die, the strangeness of early adolescence and the sweetness of a first romance, she grows in confidence and self-awareness. The characters are all very-well rounded individuals, and I think that Jidé Jackson is one of the loveliest boyfriends I've encountered in a kids' or teen book for a long time - and he's only twelve.

The artichoke of the title refer to a charm given to Mira by Nana Josie, a symbol of the human heart, and how with age and experience, a heart which may seem to break grows tough layers to protect it, like the layers of an artichoke. The novel is a sweet, beautiful coming-of-age story, showing a child starting to learn who she is. Mira is a quiet girl, artistic and thoughtful, but through the sadness of seeing her grandmother die, the strangeness of early adolescence and the sweetness of a first romance, she grows in confidence and self-awareness. The characters are all very-well rounded individuals, and I think that Jidé Jackson is one of the loveliest boyfriends I've encountered in a kids' or teen book for a long time - and he's only twelve.

|

| Read for the Support Your Local Library Challenge 2011 |

One way that Mira grows in her understanding is in her extracurricular creative writing class, which is led by writer Miss Pat Print, and consists of herself, her best friend Millie, Jidé and his friend Ben Gbemi. In the classes, Miss Print (an unfortunate name for a writer!) helps the children to understand themselves and their world through writing. The novel is written as being Mira's diary, in the present tense which itself is highlighted early on as helping reader and writer feel the immediacy of the narrative. On occasion, after a short writing exercise, the children start to feel empathy for others in a way that they hadn't before. I found these writing sessions fascinating, and they summed up what is, to me, why literature is so important: Fiction (or poetry, theatre, film, TV) helps to make sense of the world and cultivates understanding of other people.

Artichoke Hearts is a pensive, sometimes sad read, but ultimately it left me feeling uplifted, a celebration of life, youth, a loving family and good friends. I would recommend it for Judy Blume fans and older readers of Jacqueline Wilson, who are maybe looking for something a bit more grown-up. So far, Artichoke Hearts has quietly slipped onto the bookshop shelves with little fanfare, but it deserves to be widely read and talked about.

Saturday, 29 January 2011

Little Women, Louisa May Alcott

I used to be confused and a bit annoyed when film and stage adaptations of this classic story would be titled Little Women but contain the story both of Little Women and the "sequel" Good Wives. It was not until relatively recently that I discovered that Good Wives is merely the UK title for what was originally, and still is elsewhere, the second half of Little Women itself. Upon discovering this, and not being overly fond of the twee Good Wives as a title, I determined to buy my own copy of the complete text. Previously I had never got past volume one, but having a book all-in-one would get me past the usual stopping point. It seemed that a Penguin paperback would be my best bet, but in Foyle's I found a lovely hardback for a lower price.

Little Women was never one of my absolute favourite books, although I've read it a fair few times, seen the 1990s film and a West End play. It's a strange thing, but every time I read this book I seem to come to it with a different attitude, and take different things away from the reading. As a child I viewed it as similar to What Katy Did, but a bit more grown-up - possibly because I was a bit more grown-up when I first read it. I came back to it a year or two ago, intending to read the whole series, but stopped at the end of Little Women [volume one] after feeling bogged down by all the moralising. Frustrated, I found the girls too good to be true, their faults only there to be overcome and an over-keenness to be lectured by their "Marmee."

That was just about a year ago. This time around I wondered if I was reading the same book, because Meg, Jo, Beth and Amy were refreshingly real, made up not of a single fault there just to be overcome, but flesh-and-blood teenagers with understandable struggles against hot tempers, jealousy, discontent, crippling shyness among others. The girls' friendship with the boy next door, Theodore "Laurie" Laurence was refreshing for the era, a cosy, platonic companionship full of fun, games and silliness that you just don't get in Victorian literature. I noticed scenes and chapters I must have only skimmed before, because they felt quite new to me. Perhaps these were the scenes omitted from the film, of which I may have retained more memories.

That's not to say I didn't find the moralising a little heavy-handed at times. In the chapter Meg Goes to Vanity Fair, Meg is rebuked first in the text, then by Laurie and finally by Marmee, for allowing herself to be made-over by her rich friend-of-a-friend for a party, and acting the part. Looking at it one way I felt quite cross, asking "What's wrong with dressing up once in a while?" and wondering if the moral here was that one shouldn't act above one's station, an idea that appalled the twenty-first century English girl who - until very recently - had an idea that class boundaries were fairly fluid. Looking at it the other way and I know quite well what Alcott's point was. After all, I tut when watching Grease to see Sandy dressing up in her leather catsuit and smoking cigarettes just to gain the respect of someone who isn't worth it. Here, Meg is doing just the same thing (I'm just picturing her in that tight catsuit!) by pretending to be someone who she isn't, just to try to fit in. We see the same in enough high school dramas nowadays.

Similarly, I was riled in part two when Professor Bhaer - and Miss Alcott - preach about the evils of writing and reading gothic thrillers and sensational stories. (Maybe I'm just horribly degenerate.) On the other hand, Alcott satirises Jo's attempts to write the sort of sickly, moralistic Victorian fiction that makes Little Women look positively riotous, the lesson being that Jo should write for herself, write what she knows and loves, and not merely what sells - something that still holds true for writers today.

I, as well as probably most girl readers of Little Women, and certainly Alcott herself, identify best with tomboy Jo, the independant woman, the writer with the hot temper and burning ambition. As a small girl I had some sympathy with shy Beth, but nowadays she comes across not as a human being, but that device of the sicklier Victorian literature: the good girl who essentially dies of being too angelic and insipid. I have to confess I've never liked Amy very much, finding her spoilt and a bit of a snob.

Little Women was never one of my absolute favourite books, although I've read it a fair few times, seen the 1990s film and a West End play. It's a strange thing, but every time I read this book I seem to come to it with a different attitude, and take different things away from the reading. As a child I viewed it as similar to What Katy Did, but a bit more grown-up - possibly because I was a bit more grown-up when I first read it. I came back to it a year or two ago, intending to read the whole series, but stopped at the end of Little Women [volume one] after feeling bogged down by all the moralising. Frustrated, I found the girls too good to be true, their faults only there to be overcome and an over-keenness to be lectured by their "Marmee."

That was just about a year ago. This time around I wondered if I was reading the same book, because Meg, Jo, Beth and Amy were refreshingly real, made up not of a single fault there just to be overcome, but flesh-and-blood teenagers with understandable struggles against hot tempers, jealousy, discontent, crippling shyness among others. The girls' friendship with the boy next door, Theodore "Laurie" Laurence was refreshing for the era, a cosy, platonic companionship full of fun, games and silliness that you just don't get in Victorian literature. I noticed scenes and chapters I must have only skimmed before, because they felt quite new to me. Perhaps these were the scenes omitted from the film, of which I may have retained more memories.

That's not to say I didn't find the moralising a little heavy-handed at times. In the chapter Meg Goes to Vanity Fair, Meg is rebuked first in the text, then by Laurie and finally by Marmee, for allowing herself to be made-over by her rich friend-of-a-friend for a party, and acting the part. Looking at it one way I felt quite cross, asking "What's wrong with dressing up once in a while?" and wondering if the moral here was that one shouldn't act above one's station, an idea that appalled the twenty-first century English girl who - until very recently - had an idea that class boundaries were fairly fluid. Looking at it the other way and I know quite well what Alcott's point was. After all, I tut when watching Grease to see Sandy dressing up in her leather catsuit and smoking cigarettes just to gain the respect of someone who isn't worth it. Here, Meg is doing just the same thing (I'm just picturing her in that tight catsuit!) by pretending to be someone who she isn't, just to try to fit in. We see the same in enough high school dramas nowadays.

Similarly, I was riled in part two when Professor Bhaer - and Miss Alcott - preach about the evils of writing and reading gothic thrillers and sensational stories. (Maybe I'm just horribly degenerate.) On the other hand, Alcott satirises Jo's attempts to write the sort of sickly, moralistic Victorian fiction that makes Little Women look positively riotous, the lesson being that Jo should write for herself, write what she knows and loves, and not merely what sells - something that still holds true for writers today.

I, as well as probably most girl readers of Little Women, and certainly Alcott herself, identify best with tomboy Jo, the independant woman, the writer with the hot temper and burning ambition. As a small girl I had some sympathy with shy Beth, but nowadays she comes across not as a human being, but that device of the sicklier Victorian literature: the good girl who essentially dies of being too angelic and insipid. I have to confess I've never liked Amy very much, finding her spoilt and a bit of a snob.

|

| Read as Children's Classic for the Back to the Classics Challenge |

When it comes to the love stories, I'm not quite satisfied. I'm certainly not Laurie/Jo "shipper," but it seems to me that Laurie ends up with Amy simply as the next best thing, if he can't marry Jo. Jo's eventual husband Professor Bhaer is a very pleasant character, but being about twice her age, very plain and having a rather distancing title, just isn't the dashing hero I'd wish for the heroine. Meg's marriage to John Brooke, on the other hand, is portrayed very realistically with two young people as poor as the proverbial church mouse, living in the house about the size of a shoe box, madly in love, but still experiencing conflict as the honeymoon period comes to an end, with Meg accidentally neglecting her husband when being overwhelmed with coping with twins, and John happening to bring a friend home for supper on the one day Meg is having a disaster in the kitchen. Marmee steps in to offer some very wise advice, and in this context it doesn't come across as preachy, but as the calm voice of experience. Marmee is the steady force in the family, always with the right answers, but with the sympathy that comes from having been in the same fixes as her girls in her own youth.

Labels:

4*,

american civil war,

classic,

coming of age,

family,

friendship,

girls',

romance

Sunday, 16 January 2011

Anne of Avonlea, L. M. Montgomery

At sixteen and a half, Anne Shirley has finished her own schooling at Queen's Academy, and is preparing to return to Avonlea school, this time as its teacher. Though much changed from the talkative eleven-year-old adopted by Matthew and Marilla, Anne is still full of dreams and ideals, and always on the lookout for "kindred spirits." There are several newcomers to Avonlea, from the prosaic, grouchy Mr Harrison who moves in next door with his parrot, to poetic Paul Irving, kindred spirit and Anne's favourite pupil - if teachers had favourites, which of course they don't. And Marilla, who a few years ago no one would have foreseen raising one child, has taken in two more, six-year-old twins Davy and Dora Keith. As reflected in the title, the setting of the story spreads from the grounds of Green Gables, the school and surrounding woodland, to the whole village, and we get to know more of its inhabitants. As well as the next generation of Avonlea schoolchildren, we get to see more of the elder residents of the village when Anne, Gilbert and some of their other friends set up the Village Improvement Society, and through this we get to better know assorted friends-and-relations: Andrewses, Sloanes, Pyes and more. I've read this book more times than I can remember, and still can't work out who's who in Avonlea, but it's clear that Mrs Montgomery knew them all.

While just as episodic as Green Gables, the stories told in Avonlea are slightly more grown-up in theme and perhaps overall a little more sedate. Anne at sixteen to eighteen years of age seems a good deal older than I am at twenty five! Yet she is not yet cured of landing herself in embarrassing situations, such as falling through the roof of a neighbour's duck-house, and smothering her nose in red dye instead of freckle lotion before a surprise visit from a distinguished authoress. More childish amusement comes from the Keith twins, or rather Davy who always "wants to know" - Dora might as well be a porcelain doll for all the personality she is given. Paul Irving, too, is clearly intended to be a kindred spirit, though I find him a rather soppy character for a ten-year-old boy, despite Anne's and the author's protests that he is as manly as all the other boys in his class. Clearly Paul is supposed to be a reflection of Anne, with his make-believe and quirky little thoughts, but I couldn't believe in him. To me he seemed like a prototype of Walter Blythe from the later books, but Walter is more fleshed-out and his struggles make him come alive. Paul's difficulty in eating a whole dish of porridge doesn't quite work as a character flaw.