Looking back over the hundred-plus books I've read this year, I was surprised to see which books had stuck in my mind and how many I had forgotten ever reading - or at least, was surprised to discover I had read them only this year. I've paid flying visits through some story-worlds, and immersed myself in others, which were often but not necessarily the ones I enjoyed the most at the time.

It can be a wonderful but slightly frightening thing to be so engrossed in a story that it is more real than day-to-day life. The notable books and series for this in 2012 were:

The Sandman graphic novel series by Neil Gaiman. Can that really have been this year? It seems a lifetime ago.

Sherlock Holmes by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, prompted by the BBC's second series of Sherlock at New Year. (Towards the end of the year I once more immersed myself in the world of 221B Baker Street by watching the second Holmes movie from last year, and having another Sherlock marathon.

My reread of Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit, around the middle of the year, reignited a second time by receiving a lot of the Lego sets for my birthday, and a third by the release the first Hobbit film. Middle-Earth has had a strong pull on me since I was 16, and it doesn't like to let me go.

A Song of Ice and Fire. I took a long time to even be tempted to read this series of doorstopper novels, but eventually I was won around - although I have second thoughts about whether or not to watch the TV adaptation.

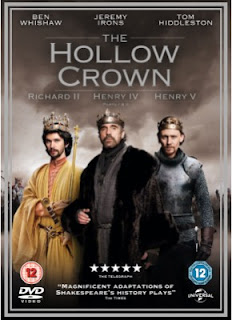

Shakespeare as a whole, although I've only actually read the one play in its entirety this year - Julius Caesar. The BBC's marvelous Hollow Crown was a magnificent introduction to Shakespeare's history plays - I love the tragedies, and some of the comedies, but apart from studying the famous bits of Henry V, the histories were entirely new to me. But the staging of Richard II, Henry IV and Henry V utterly captured my mind and admiration in the way only the Bard can do.

Other books that have stuck in my brain:

The Fault in our Stars - John Green.

The Etymologicon - Mark Forsyth (look! A non-fiction!)

The Snow Child - Eowyn Ivey

Tipping the Velvet - Sarah Waters

Little Brother - Cory Doctorow

The Perks of Being A Wallflower - Stephen Chbosky

1Q84 - Haruki Murakami

Perfume: The Story of a Murderer - Patrick Suskind

But looking back over my reading, I realise how much I've already forgotten; how many books that I enjoyed while I read them but which didn't stick in my mind, and the books that I was fairly indifferent to, and how relatively few really engaged me as a reader. And there is a place for light reading, for enjoyable fluff, but I found myself wondering how many books were ones which I read because they were short or easy, and because I hadn't posted a review on my blog for ages. Surprise, surprise, the easy reads often didn't get reviewed either, because I hadn't much to say about them.

Ellie at Musings of a Bookshop Girl wrote an excellent series of posts about rediscovering the joy of reading which I recommend reading if you feel you've fallen into a bit of a reading or blogging slump. Quality, rather than quantity, is my aim for reading and reviewing in 2013. Of late I have not done much of either. And by "Quality" I don't mean reading only Serious Literature and shunning light reading - far from it! At heart I am a fantasy freak. A thriller-seeker. A comfort-reader. A girl with a literature degree and the intent to use it. A nostalgic inner child. All these things at once and more. My aim is to merely to read the books I love, not the page-numbers of those I don't.

I set myself two reading challenges in 2012 - to read 120 books in a year (at the time of writing I have just over 5 books left to read in under 29 hours - not going to happen!) and Ellie's Mixing It Up Challenge, which encouraged me to read outside my comfort zone. In the end I read books in 13 of 16 genres - you can see which ones here - so I missed target but hardly disgraced myself, and seem to have more non-fiction in my list than in most years. But for 2013 I have resolved to set myself no blogging/reading challenges at all - not even enabling a target on Goodreads for how many books to read. That in itself feels like a bit of a scary commitment as I've been setting myself challenges for several years now (and failing to meet any of my targets.) I'm going to be selfish, and I'm going to fall back in love with my books once more.

At the same time, one of Gandalf's lines in the new Hobbit film really struck a chord with me: The world is out there, not in your books and maps. Or as Dumbledore would put it, It does not do to dwell on dreams and forget to live. So in 2013, I want to go on my own adventures. What form these may take is as yet a mystery, but I feel the need to redress the balance between book and life.

Happy new year everyone, and I wish you all lots of joy for 2013.

Sunday, 30 December 2012

Sunday, 23 December 2012

Book to Film: The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey

This is going to be a looooong one. Spoilers for the film, but not later on in the book.

It's always risky adapting a beloved film for the big screen. They say that no two people read the same book; everybody has their own ideas about how it should look, sound and feel. Even Peter Jackson, whose adaptation of J.R.R. Tolkien's Lord of the Rings was widely acclaimed, was not guaranteed to repeat his success upon his return to Middle-Earth. One could be forgiven for thinking that after the sprawling three-volume epic, The Hobbit should be a piece of cake, but the smaller novel provides its own challenges. In effect, it has to be two different stories simultaneously: the simple fairy-tale that Tolkien started writing while marking exam papers, and a part of an entire world of mythology that culminated in the Lord of the Rings. The Hobbit's reviews have been very mixed, and those negative reviews that are not primarily concerned with Jackson's experiments with frame-rates, seem to fall in one of two camps. Some complain that The Hobbit is too much like Lord of the Rings, too epic and complex, when it ought to be a Narnia-esque kids' adventure. Others think that it is too simple and childish - not enough like LotR.

Me? I couldn't be happier. As far as I'm concerned, Jackson got the balance just right, keeping the world of The Hobbit consistent with the existing cinematic Middle-Earth, but retaining the story's unique flavour. At first I had my doubts about the wisdom and necessity of turning The Hobbit into two films, let alone three, but after reading the book I realised just how much happens, how many people Bilbo, Thorin and co meet, and how many places they visit, rushed through at a chapter per location, character or incident. It would be a very long film to do each one justice. Jackson and co have also turned to the back end of LotR's appendices and other writings to give an added depth to The Hobbit.

The film opens with a prologue, slotting it nicely into the beginning of Fellowship of the Ring, by showing Bilbo Baggins as an old Hobbit, and a cameo from Frodo. Perhaps this is a little forced, but it rekindles that homey feeling of Bag End, and was probably put in as an excuse to show Bilbo writing and narrating those immortal words:

J.R.R. Tolkien didn't give the Dwarves a lot of personality, with the exception of the king, Thorin Oakenshield. Balin is kind, Dori is "a decent fellow," Fili and Kili are young, cheerful and a bit reckless, and Bombur is overweight - that's about all we know. For the film, each of the thirteen has his own look and personality trait. Fili and Kili are shaping up to be fan favourites - especially among the female fans, perhaps for obvious reasons.

May I here point out that they were always my favourites, years before they were cast? Fili, Kili and Balin, who is depicted in the film as a gentle soul but a seasoned warrior, a loyal follower of Thorin, but one filled with doubts about the wisdom of their quest to reclaim the Lonely Mountain of Erebor.

An unexpected favourite from the movie adaptation turned out to be Bofur (played by James Nesbitt) who has been expanded from one of the Interchangeable Backup Dwarves to quite a character. He starts off as quite a lovable rascal with a Northern Irish accent and a twinkle in his eye, tormenting Bilbo in his home and sparing no details about exactly how it would feel to run into the business end of Smaug* the dragon. Yet, a moving scene later on in the film proves that he is made up entirely of charm and loveliness.

Reading the book, I never found Dwarven king Thorin Oakenshield to be a very likeable character, surly at best and a complete jerk at worst, but, again, the movie rounds him out a little by showing flashbacks to his past. After showing the devastation of Erebor and the awful aftermath of battles, his quest comes across as more than filling his pockets with gold. I still wanted to shout "Oh, shut up Thorin!" a couple of times, but not as often as when reading the book.

Like Lord of the Rings, The Hobbit uses long, panning shots of breathtaking New Zealand countryside that made me want to pack up my bags and hop on a plane to go on long treks across the mountains. Howard Shore returned to compose the score, keeping in the heartachingly familiar Concerning Hobbits theme, and giving it a jaunty and adventurous twist in keeping with Bilbo's character. As well as other familiar leitmotifs, Shore has introduced some new tunes, most notably the solemn, proud, Dwarf theme (the same tune used in the "Misty Mountains" song which reduced many a Tolkien fan to tears in the first Hobbit trailer last year.) The soundtrack and scenery help to ground this story in the same Middle-Earth as Rings, leaving me feeling as though I'd never left.

It is interesting to compare the perspectives of the Hobbit and the Lord of the Rings quests. LotR focused upon the human civilisations and the Elves, whose glory days were coming to an end, and the beauty of their kingdoms in Rivendell and Lothlorien, but the only Dwarf, Gimli, was mainly used for comic relief. We return once more to Rivendell, but somehow it doesn't feel like the same idyllic haven that it was before. In the company of Dwarves, we see through their eyes, and I felt that Jackson excelled in subtly giving the same place a sense that something was slightly off-kilter in this golden leafy paradise. The Elves do not sing "tra-la-la-lally," (thank goodness!) but there is a tra-la-la-lally feel to their music, that is at odds with the solid, earthy Dwarves. That being said, I enjoyed seeing another side to Elrond: riding home exhilarated from battling goblins, not the care-worn, frowning leader bearing responsibility for the whole world as well as his wayward daughter.

But it was in Rivendell that I had the closest thing to a criticism of the film: the role of Galadriel. My quibble was not with anything explicitly said or done, so much as the veneration with which Galadriel was treated. Yes, she is one of the wisest beings on Middle-Earth, and, though she is not mentioned in the book of The Hobbit, the Lord of the Rings and Unfinished Tales establish her as being a key member of the White Council. But she is still an Elf. The film adaptation implied in its treatment that she ranked higher even than Gandalf, but the wizards of Middle-Earth are in fact closer to angels than humans or Elves. Still, if these suggestions and insinuations are my only cause for complaint - and "complaint" is far too strong a word, really - then The Hobbit fares better than both The Two Towers and Return of the King, which in turn are nearly flawless despite each containing a moment that makes me shout at the TV every time. +

The great enemy of The Hobbit is, of course, Smaug the dragon, but he barely makes an appearance in the first part of the film - just flashes of stamping feet, swooshing tail and a single golden eye. But there are other foes that Bilbo and the Dwarves must face in the form of the trolls and goblins. These seem to jar a little in comparison to the evil creatures we have previously encountered in Middle-Earth, and it was very strange to watch the trolls sitting around the campfire grumbling and talking. The Great Goblin is quite jolly in a nasty sort of way, even singing a happy little song about how he intends to send the Dwarves to a gruesome fate. Such moments remind us that The Hobbit is a children's story, and yet at the same time, the villains are more complex than the Lord of the Rings orcs, with distinct personalities (albeit not particularly pleasant ones) which may cause a bit of a twinge of disconcerting pity when they get killed. There is a poignant moment when the blue glow of Bilbo's sword, an alert to the presence of goblins, fades away, the goblin having been killed by Gollum. It is strange and unsettling to feel pity for the orcs - battles against them were simple and straightforwardly good-versus-evil in the more "grown-up" Lord of the Rings. Yet that moment of pity foreshadows the critical turning-point in the entire Ring saga: when Bilbo Baggins did not kill Gollum.

It is not only the Hobbit's monsters' characters that seem a little out of place with how we've seen them so far in the cinematic Middle-Earth, but also their appearance. It is apparent that a lot more CGI has been used in the creation of the goblins, and perhaps also the trolls, than in Lord of the Rings. LotR was, of course, a big turning point in computer graphics in the movies, with Gollum a pioneer in motion capture technology. But whereas Gollum fits right at home among the other cast, thanks to the character's design and Andy Serkis' extraordinary acting skills, some of the Hobbit's CGI antagonists don't look as real as the old-style orcs which were actors in prosthetics. I thought that there was something slightly off about the Pale Orc, Azog, but it wasn't until my second viewing that I realised why. It was not merely that computer graphics look less solid than the real thing, but Azog, as well as one or two of the other creatures, looked like they had wandered off the set of Guillermo Del Toro's Pan's Labyrinth - probably no coincidence, as Del Toro also worked on The Hobbit.

Gollum, of course, stole the show, and I was saddened at the end of the film to remember that he only featured in the single chapter of the book and would not be seen again until Lord of the Rings. He is, as ever, alternately hilarious, cute and pathetic, but my friend and I agreed that we also got more of a sense of menace from him than in his previous appearances. Frodo, of course, knew of Gollum before their first meeting, but Bilbo was unprepared, alone and terrified, and he first sees Gollum violently killing a goblin twice his size. Freeman's and Serkis' acting in their game of riddles is marvellous, bringing the book to life in a bit of light relief but with an undercurrent of tension beneath.

When Gollum discovers the loss of his "precious," the light relief is gone. The Ring is Gollum's sole reason for being, and its loss seems unendurable. But Gollum will go on hunting it for the next sixty years - or seventy-seven if you go by the book's chronology. Gollum's agony is heartbreaking, and the expressions changing from terror to compassion on Bilbo's face will stay with me for a long, long time. The entire saga depends on that single moment, and it could not have been done better. It was perfection itself.

I still don't care for 3D, though. I'm unsure whether the edition I watched on Friday 14th was the infamous double-frame-rate version of the film or not (I'm no expert in that sort of thing, being more concerned about the story, scripting and acting) but I did find it difficult to focus during the busy action scenes. The 3D is certainly well done, but I found it to be more of a distraction than an enhancement. There was one notable moment when I thought that a member of the audience had stood up in the aisle and blocked the screen, until I realised that it was a 3D character on the edge of the shot.

After Lord of the Rings, I hadn't been too excited about the possibility of a Hobbit film, and doubted the necessity of making more than one - after all, it is shorter than any one LotR volume. Yet despite its simplicity, it is a very full book, as I realised on my recent reread. Are three films really necessary? Well, I've no doubt that there are parts of An Unexpected Journey that could be trimmed with little detriment to the finished result, and I would have estimated that Jackson could probably have made two decent movies without sacrificing any plot. Yet if parts two and three are up to this standard, then as far as I'm concerned, the more Hobbit film there is, the better. (Bring on the Extended DVD!) An Unexpected Journey was an absolute joy to watch - though I strongly advise you to avoid drinking anything before or while watching it. I have already seen the movie twice, and expect to see it at least one more time. Probably more.

*I've been pronouncing it "Smorg" all these years, but apparently the "au" makes an "ow" sound. Similarly, the film rhymes "Thorin" with "Florin" but I've always called him "Thor-in."

+the Faramir-fail and the Sam-go-home-fail, if you're interested.

It's always risky adapting a beloved film for the big screen. They say that no two people read the same book; everybody has their own ideas about how it should look, sound and feel. Even Peter Jackson, whose adaptation of J.R.R. Tolkien's Lord of the Rings was widely acclaimed, was not guaranteed to repeat his success upon his return to Middle-Earth. One could be forgiven for thinking that after the sprawling three-volume epic, The Hobbit should be a piece of cake, but the smaller novel provides its own challenges. In effect, it has to be two different stories simultaneously: the simple fairy-tale that Tolkien started writing while marking exam papers, and a part of an entire world of mythology that culminated in the Lord of the Rings. The Hobbit's reviews have been very mixed, and those negative reviews that are not primarily concerned with Jackson's experiments with frame-rates, seem to fall in one of two camps. Some complain that The Hobbit is too much like Lord of the Rings, too epic and complex, when it ought to be a Narnia-esque kids' adventure. Others think that it is too simple and childish - not enough like LotR.

Me? I couldn't be happier. As far as I'm concerned, Jackson got the balance just right, keeping the world of The Hobbit consistent with the existing cinematic Middle-Earth, but retaining the story's unique flavour. At first I had my doubts about the wisdom and necessity of turning The Hobbit into two films, let alone three, but after reading the book I realised just how much happens, how many people Bilbo, Thorin and co meet, and how many places they visit, rushed through at a chapter per location, character or incident. It would be a very long film to do each one justice. Jackson and co have also turned to the back end of LotR's appendices and other writings to give an added depth to The Hobbit.

The film opens with a prologue, slotting it nicely into the beginning of Fellowship of the Ring, by showing Bilbo Baggins as an old Hobbit, and a cameo from Frodo. Perhaps this is a little forced, but it rekindles that homey feeling of Bag End, and was probably put in as an excuse to show Bilbo writing and narrating those immortal words:

In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.Corny set-up or not, those words would have been missed if they had not been there. The entire Bag End scenes which follow are practically flawless. Martin Freeman truly is the young Bilbo Baggins. I fear Mr Freeman may be in danger of being typecast as an ordinary Englishman (or hobbit of the Shire) who finds himself caught up in extraordinary adventures against his will - see Sherlock's Dr Watson, or Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy's Arthur Dent. But he plays these roles so beautifully! Bilbo and Gandalf's first interaction walked straight off the page and onto the screen, a lighter comedy than in even the beginning of Fellowship of the Ring, and laying to rest my anxieties that this would be more Lord of the Rings: The Prequel than The Hobbit. After this very strange encounter with a wizard who seem to know more about Mr Baggins than he ought, poor Bilbo finds his house swarming with Dwarves, with muddy boots, sharp swords and huge appetites, completely clearing out his pantry and threatening to trash his kitchen. (Spoiler alert: Yes, the washing-up song is in there - one of my favourite moments in the entire film.)

J.R.R. Tolkien didn't give the Dwarves a lot of personality, with the exception of the king, Thorin Oakenshield. Balin is kind, Dori is "a decent fellow," Fili and Kili are young, cheerful and a bit reckless, and Bombur is overweight - that's about all we know. For the film, each of the thirteen has his own look and personality trait. Fili and Kili are shaping up to be fan favourites - especially among the female fans, perhaps for obvious reasons.

May I here point out that they were always my favourites, years before they were cast? Fili, Kili and Balin, who is depicted in the film as a gentle soul but a seasoned warrior, a loyal follower of Thorin, but one filled with doubts about the wisdom of their quest to reclaim the Lonely Mountain of Erebor.

An unexpected favourite from the movie adaptation turned out to be Bofur (played by James Nesbitt) who has been expanded from one of the Interchangeable Backup Dwarves to quite a character. He starts off as quite a lovable rascal with a Northern Irish accent and a twinkle in his eye, tormenting Bilbo in his home and sparing no details about exactly how it would feel to run into the business end of Smaug* the dragon. Yet, a moving scene later on in the film proves that he is made up entirely of charm and loveliness.

Reading the book, I never found Dwarven king Thorin Oakenshield to be a very likeable character, surly at best and a complete jerk at worst, but, again, the movie rounds him out a little by showing flashbacks to his past. After showing the devastation of Erebor and the awful aftermath of battles, his quest comes across as more than filling his pockets with gold. I still wanted to shout "Oh, shut up Thorin!" a couple of times, but not as often as when reading the book.

Like Lord of the Rings, The Hobbit uses long, panning shots of breathtaking New Zealand countryside that made me want to pack up my bags and hop on a plane to go on long treks across the mountains. Howard Shore returned to compose the score, keeping in the heartachingly familiar Concerning Hobbits theme, and giving it a jaunty and adventurous twist in keeping with Bilbo's character. As well as other familiar leitmotifs, Shore has introduced some new tunes, most notably the solemn, proud, Dwarf theme (the same tune used in the "Misty Mountains" song which reduced many a Tolkien fan to tears in the first Hobbit trailer last year.) The soundtrack and scenery help to ground this story in the same Middle-Earth as Rings, leaving me feeling as though I'd never left.

It is interesting to compare the perspectives of the Hobbit and the Lord of the Rings quests. LotR focused upon the human civilisations and the Elves, whose glory days were coming to an end, and the beauty of their kingdoms in Rivendell and Lothlorien, but the only Dwarf, Gimli, was mainly used for comic relief. We return once more to Rivendell, but somehow it doesn't feel like the same idyllic haven that it was before. In the company of Dwarves, we see through their eyes, and I felt that Jackson excelled in subtly giving the same place a sense that something was slightly off-kilter in this golden leafy paradise. The Elves do not sing "tra-la-la-lally," (thank goodness!) but there is a tra-la-la-lally feel to their music, that is at odds with the solid, earthy Dwarves. That being said, I enjoyed seeing another side to Elrond: riding home exhilarated from battling goblins, not the care-worn, frowning leader bearing responsibility for the whole world as well as his wayward daughter.

But it was in Rivendell that I had the closest thing to a criticism of the film: the role of Galadriel. My quibble was not with anything explicitly said or done, so much as the veneration with which Galadriel was treated. Yes, she is one of the wisest beings on Middle-Earth, and, though she is not mentioned in the book of The Hobbit, the Lord of the Rings and Unfinished Tales establish her as being a key member of the White Council. But she is still an Elf. The film adaptation implied in its treatment that she ranked higher even than Gandalf, but the wizards of Middle-Earth are in fact closer to angels than humans or Elves. Still, if these suggestions and insinuations are my only cause for complaint - and "complaint" is far too strong a word, really - then The Hobbit fares better than both The Two Towers and Return of the King, which in turn are nearly flawless despite each containing a moment that makes me shout at the TV every time. +

Galadriel is not the only character to be moved to The Hobbit from Tolkien's works. For the first time, we are introduced to Radagast the Brown, a third member of the order of Istari (commonly known as wizards.) Sylvester McCoy (familiar to many as the Seventh Doctor) portrays Radagast as a rather dotty character, with a darling little pet hedgehog named Sebastian - not a name that you could derive from any of Tolkien's languages, but one which suits the hedgehog perfectly. But I digress. Hidden beneath Radagast's silly exterior which earns ridicule from the haughty Saruman and certain critics, are strength, wisdom and courage equal to that of his peers. "Is he a great wizard?" Bilbo asks Gandalf, "Or is he more like you?" "I think he is a very great wizard," is Gandalf's answer, and I think I would prefer to take Gandalf's side on this matter than Saruman's. Power corrupts absolutely, as is proven by Saruman later on in Lord of the Rings, but there is an innate innocence to Radagast that prevents this in his case.

The great enemy of The Hobbit is, of course, Smaug the dragon, but he barely makes an appearance in the first part of the film - just flashes of stamping feet, swooshing tail and a single golden eye. But there are other foes that Bilbo and the Dwarves must face in the form of the trolls and goblins. These seem to jar a little in comparison to the evil creatures we have previously encountered in Middle-Earth, and it was very strange to watch the trolls sitting around the campfire grumbling and talking. The Great Goblin is quite jolly in a nasty sort of way, even singing a happy little song about how he intends to send the Dwarves to a gruesome fate. Such moments remind us that The Hobbit is a children's story, and yet at the same time, the villains are more complex than the Lord of the Rings orcs, with distinct personalities (albeit not particularly pleasant ones) which may cause a bit of a twinge of disconcerting pity when they get killed. There is a poignant moment when the blue glow of Bilbo's sword, an alert to the presence of goblins, fades away, the goblin having been killed by Gollum. It is strange and unsettling to feel pity for the orcs - battles against them were simple and straightforwardly good-versus-evil in the more "grown-up" Lord of the Rings. Yet that moment of pity foreshadows the critical turning-point in the entire Ring saga: when Bilbo Baggins did not kill Gollum.

It is not only the Hobbit's monsters' characters that seem a little out of place with how we've seen them so far in the cinematic Middle-Earth, but also their appearance. It is apparent that a lot more CGI has been used in the creation of the goblins, and perhaps also the trolls, than in Lord of the Rings. LotR was, of course, a big turning point in computer graphics in the movies, with Gollum a pioneer in motion capture technology. But whereas Gollum fits right at home among the other cast, thanks to the character's design and Andy Serkis' extraordinary acting skills, some of the Hobbit's CGI antagonists don't look as real as the old-style orcs which were actors in prosthetics. I thought that there was something slightly off about the Pale Orc, Azog, but it wasn't until my second viewing that I realised why. It was not merely that computer graphics look less solid than the real thing, but Azog, as well as one or two of the other creatures, looked like they had wandered off the set of Guillermo Del Toro's Pan's Labyrinth - probably no coincidence, as Del Toro also worked on The Hobbit.

Gollum, of course, stole the show, and I was saddened at the end of the film to remember that he only featured in the single chapter of the book and would not be seen again until Lord of the Rings. He is, as ever, alternately hilarious, cute and pathetic, but my friend and I agreed that we also got more of a sense of menace from him than in his previous appearances. Frodo, of course, knew of Gollum before their first meeting, but Bilbo was unprepared, alone and terrified, and he first sees Gollum violently killing a goblin twice his size. Freeman's and Serkis' acting in their game of riddles is marvellous, bringing the book to life in a bit of light relief but with an undercurrent of tension beneath.

"If Baggins loses, then we eat it whole?"

"...Fair enough."

When Gollum discovers the loss of his "precious," the light relief is gone. The Ring is Gollum's sole reason for being, and its loss seems unendurable. But Gollum will go on hunting it for the next sixty years - or seventy-seven if you go by the book's chronology. Gollum's agony is heartbreaking, and the expressions changing from terror to compassion on Bilbo's face will stay with me for a long, long time. The entire saga depends on that single moment, and it could not have been done better. It was perfection itself.

I still don't care for 3D, though. I'm unsure whether the edition I watched on Friday 14th was the infamous double-frame-rate version of the film or not (I'm no expert in that sort of thing, being more concerned about the story, scripting and acting) but I did find it difficult to focus during the busy action scenes. The 3D is certainly well done, but I found it to be more of a distraction than an enhancement. There was one notable moment when I thought that a member of the audience had stood up in the aisle and blocked the screen, until I realised that it was a 3D character on the edge of the shot.

After Lord of the Rings, I hadn't been too excited about the possibility of a Hobbit film, and doubted the necessity of making more than one - after all, it is shorter than any one LotR volume. Yet despite its simplicity, it is a very full book, as I realised on my recent reread. Are three films really necessary? Well, I've no doubt that there are parts of An Unexpected Journey that could be trimmed with little detriment to the finished result, and I would have estimated that Jackson could probably have made two decent movies without sacrificing any plot. Yet if parts two and three are up to this standard, then as far as I'm concerned, the more Hobbit film there is, the better. (Bring on the Extended DVD!) An Unexpected Journey was an absolute joy to watch - though I strongly advise you to avoid drinking anything before or while watching it. I have already seen the movie twice, and expect to see it at least one more time. Probably more.

*I've been pronouncing it "Smorg" all these years, but apparently the "au" makes an "ow" sound. Similarly, the film rhymes "Thorin" with "Florin" but I've always called him "Thor-in."

+the Faramir-fail and the Sam-go-home-fail, if you're interested.

Labels:

5*,

adaptation,

book to film,

epic,

fantasy,

Hobbits,

kids' classics,

Tolkien

Sunday, 9 December 2012

Perfume: The Story of a Murderer - Patrick Süskind

Just these last few weeks, it has seemed as though the whole world wanted me to read Patrick Süskind's Perfume: The Story of a Murderer. After joining in with a customer about the merits of real books over e-readers, his parting words to me were to recommend this book. My friend had been talking about the movie adaptation, and then Ellie mentioned it as a really challenging book in reply to my comment on one of her posts. Lastly, it emerged that my latest acting "discovery" Ben Whishaw had starred in the movie adaptation. And I couldn't see the film without having read the book. Only Shakespeare is exempt from that.

Just these last few weeks, it has seemed as though the whole world wanted me to read Patrick Süskind's Perfume: The Story of a Murderer. After joining in with a customer about the merits of real books over e-readers, his parting words to me were to recommend this book. My friend had been talking about the movie adaptation, and then Ellie mentioned it as a really challenging book in reply to my comment on one of her posts. Lastly, it emerged that my latest acting "discovery" Ben Whishaw had starred in the movie adaptation. And I couldn't see the film without having read the book. Only Shakespeare is exempt from that.Perfume starts slowly. Really slowly. We are treated to pages and pages of descriptions of smells, every scent in Paris that you might be able to think of. Scent is, of course, a hugely evocative sense, and this forms the basis of the novel, however, I'm not quite sold on how convincingly it can be described with pen and ink. But though slow, these descriptive pages are compelling. It is easy to describe the appearance of things, but there are all the other senses, and Süskind has chosen to focus on one not widely used in literature.

Jean-Baptiste Grenouille, Perfume's protagonist villain, is a very unusual sort of character, even from birth. Those who ought to look after the infant Grenouille are repelled by him in ways they cannot describe, other than that he smells of nothing. Yet his own nose is remarkable, able to identify the subtlest scents, and this one sense occupies his entire mind. He is utterly alien, lacking in human qualities, a psychopathic nose. There is nothing relatable about Grenouille, and yet he is pitiable. Süskind seems to use scent as a metaphor for the soul, and Perfume leads one to ponder on the nature-versus-nurture debate, presenting the uncomfortable idea of a person innately evil. Grenouille moves from place to place, and bad things happen to those he leaves behind. No explicit connection is made, but Grenouille leaves a trail of misfortune behind him, leading back even to his mother, which adds to the sense of menace.

Perfume does not end where you might think it should, and I found the expected denouement to be anticlimactic. When compared with the pages of description earlier in the book, the "finale" is prosaically described, lacking all tension. There is a sense of inevitability of events, with Süskind making no attempts to keep the reader guessing. I came to realise (thanks to my friend's comments) that this is actually incredibly clever, because, after all, this is how Grenouille sees the world. The smells are everything - human actions, life and death, mean nothing to him.

But just when I thought the ending was all wrapped up, the plot takes a horrifying turn by showing not just the evil in Grenouille's character, but the depravity he inspires in his fellow man by the seeming of purity. Perfume is a slow-burning novel, which took its time to grab my attention, but one that lingers, turning out very dark and unsettling indeed.

Labels:

4 buttons,

crime,

dark,

disturbing,

France,

gothic,

historical,

in translation,

literary

Friday, 7 December 2012

1Q84, Haruki Murakami

The year is 1Q84. This is the real world, there is no doubt about that. But in this world, there are two moons in the sky. In this world, the fates of two people, Tengo and Aomame, are closely entwined. They are each, in their own way, doing something very dangerous. And in this world, there seems no way to save them both. Something extraordinary is starting.

This review could be considering spoilery, if the above book blurb is all you have to go on.

1Q84 follows the lives of two characters, Aomame and Tengo, who are living very different lives in Tokyo. Aomame is a fitness trainer who doubles as an assassin, and who finds her world ever so slightly but significantly wrong after taking a shortcut off the expressway when running late for an "appointment. Tengo is an aspiring writer with a part-time job as a mathematics teacher at a girls' school. When offered the morally dubious task of rewriting a fantasy novel by an enigmatic child prodigy for a literary competition, Tengo finds himself embroiled deeper and deeper in trouble that has little to do with the legal ramifications of fraud. To his dismay, he starts to realise that this extraordinary tale of "Little People," who spin air chrysalises to hatch - essentially - changelings, a secretive cult, and a world with two moons, is not fantasy at all, but autobiography. And the Little People did not want to be written about.

Murakami keeps you guessing about how Tengo and Aomame's stories fit together, as they spend much of the book going about their lives without any kind of interaction or indication that they have ever met. Their worlds don't fit together neatly at first, and in fact I wondered at least once whether they even inhabited the same reality. There are parallels between the two characters' lives, and I would be just on the verge of thinking I knew how they worked when a small detail would seem to throw me off the scent again. The world, or worlds, of 1Q84 shifted and were just a little off-kilter for a while, before Murakami began to answer the questions raised.

The influence of Murakami's "Little People" can be felt throughout the novel, though they are rarely seen and never explained. Are they malevolent fairies or demons? When we do actually meet them, it is in a haunting, surreal scene that unsettles the mind for a long time afterwards. Despite the vagueness of the "Little People," they seemed more vivid and real than any other part of the story - it felt impossible to me that the human mind could make this up. In a New York Times interview, Murakami explained that "The Little People came suddenly. I don’t know who they are. I don’t know what it means. I was a prisoner of the story. I had no choice. They came, and I described it. That is my work." An unsettling thing to read, considering the catastrophic consequences of writing about the Little People in 1Q84. Within the book, Murakami blurred the lines between fiction and reality so well that it even spills into the mind of the reader.

The world of 1Q84 really held my imagination for a long time after I finished reading it, but the story itself was far from flawless. In three volumes, it is too long, with a lot of unnecessary exposition - book 3 introduces a character whose main role is to discover all the things the reader already knows. The characters often don't act or think like real people at all, but are quite clearly doing what they have to in order to fit the plot, rather than the plot evolving naturally from the characters' actions, and the leaps of logic with which characters solve mysteries are ridiculous. Tengo has a memory of Aomame, as a child, looking at the moon, and takes this thought as a message that he needs to look at the moon - and wait! There are two moons! Which automatically means a lot of other things are instantly to be taken as fact, not fiction. Characters somehow arrive at unlikely but true conclusions with very little reason to lead them there, and Aomame "just knows" an impossible thing can only be caused by another, specific, impossible thing.

And, though I can believe in Little People, parallel universes and two moons, I cannot suspend my disbelief enough to be convinced that two people, who interacted precisely once, twenty years ago, in fifth grade, can have a "connection" that means that they are each other's lost love, destined to be together.

All in all, I had a love-hate relationship with 1Q84. It began and ended well, and was full of extraordinary moments. I felt a thrill every time Aomame noticed something not-quite-right about her new world, and the Little People were among the weirdest things I've read in recent times. But ultimately, the questions were more satisfying to see asked than answered, and the fantasy world was more interesting than the characters or the story itself.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)